“Each person, each illness, is a particular story … full of sacred meaning.” Mary C. Earle

BEING SICK RUDELY INTERRUPTS LIFE

In the summer of 1995, I returned from a vacation in northern California. I was feeling well and relaxed from my time away. So, I had no idea that an attack of acute pancreatitis was about to change my life completely.

The Sunday prior to the attack, I felt fine. I went about my regular duties as a parish priest. On Monday, after having breakfast and sending my husband off to work, I became violently ill. I was so ill that I could barely make it to the telephone. A ride in an ambulance followed, then a hospitalization. Months of snail-slow recovery ensued. Then there was yet another attack and hospitalization with even more months of recovery.

Throughout all of this I discovered what everyone who suffers from illness in its acute, chronic, or progressive forms eventually learns: being sick rudely interrupts life as you know it. Plans, hopes, dreams – everything from trips abroad to new employment to advanced college degrees to enjoyment of grandchildren – all go by the wayside. Life changes color, tone, and texture. You make the acquaintance of something that is “other,” that lives within the housing of your body. Illness forces you to inhabit a reality that our culture rejects completely. This is a reality marked by real limitation, physical frailty, and a variety of constraints that curtail your activities.

In the hospital following my first attack, friends, parishioners, and fellow clergy came to see me. Rare was the visitor who didn’t come with an interpretation – almost all unhelpful – of my illness …

UNSOLICITED ADVICE

At a time when I was at my most vulnerable, the opinions and interpretations of others besieged me. The avalanche of unsolicited advice surprised me. So many notions of the meaning of the experience of falling acutely ill overwhelmed me. In the long months of recovery, I began to search for a way to read my illness and my body on my own. I wanted to allow myself – and other people like me – the chance to study the narrative, or the story, of what had happened. Then to bring that narrative into prayer and reflection. The quick and ready interpretations so often handed to someone who is ill overlook the specific reality of each person. It overlooks the particular experience of being ill and weakened.

If you’ve lived with illness, you know exactly what it’s like when other people so readily interpret your experience. But you have the capacity, with support, to interpret it yourself. Let the experience become a sacred text. Let it be a life narrative full of meaning – even if the meaning is veiled. Yes, even if your plans are interrupted and even if you live in wrenching pain.

Your body may give you many clues about what this illness means in your life. These clues shouldn’t be met with formulaic responses that stop your story before it is told. The text of your illness is embedded within the text of your life. It is your particular life with your own particular questions, hopes, dreams, griefs, and aspirations.

LECTIO DIVINA

As I recovered from my attacks I pondered how to re-vision my illness and my life. Then I realized that one of my own prayer practices could help me. For years the practice of lectio divina, or sacred reading, has fed my spiritual life. Why couldn’t it nourish the life and spirit of my body as well?

In the late 1970s a friend lent me audiotapes of a retreat led by the Reverend Mark Dyer. He later became the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. On those tapes, he introduced the Benedictine practice of lectio divina. It is a way of reading and praying Scripture. I clearly remember standing in the kitchen, chopping vegetables for a salad while listening as he spoke. As I went about the ordinary activity of preparing dinner, his voice described the activity of regularly engaging Scripture with an open heart.

I stood in the space so regularly inhabited by my family. And it began to dawn on me that this way of praying was intended for those who were not experts. Lectio divina was a way to listen to God through Scripture for someone like me, a mom with two small children. Bishop Dyer’s voice, at once lighthearted and learned, hinted at the formative nature of lectio divina. It became a regular way of praying for me. From time to time I tried other forms. But inevitably, I was drawn back to lectio as the basis for ongoing prayer as a way to encounter the living presence of God through Scripture.

LECTIO INVITES US TO THE SCRIPTURAL BANQUET

In a fast-food culture, lectio invites us to the scriptural banquet. It invites us to savor the richness of what we are offered, to dally at the table. With lectio we read slowly. It allows ourselves time to digest and absorb our spiritual food. Because it is reflective and slow, lectio leads us gently away from pat answers and smug conclusions. Over time, lectio leads us into the path of life. It leads us into a way of knowing that is marked by knowing how much we do not know.

Lectio shapes us in such a way that we begin to perceive our lives and their contexts in a new way. We begin to see that the living Word is present within and through the events of our lives. Lectio divina invites us to read the text of our lives and to listen to what is occurring. It invites us to approach both our personal and our corporate lives with care and attention. At that point, we discover that our lives are, in fact, a scripture in and of themselves, a story that is unfolding day by day.

My interest in finding a new way to understand and live with illness is not only personal, but professional. As a parish priest I spend a lot of time offering spiritual direction to others who live with illness. I hear many stories that are very much like mine. Those who are ill are often on the receiving end of boundless advice on how to think and feel about their experience. While often well intended, the advice has the effect of obscuring or covering over the feelings of the person who is ill. The unsolicited counsel tends to have an anxious edge to it or a “fix-it” tone.

Why this rush to interpret illness or offer advice?

Maybe this need to pinpoint the meaning of illness speaks volumes about our unease with the fact that we can weaken and die. Within Christian circles especially, there may be a strange anxiety when sick people aren’t cured: maybe they just don’t have enough faith, or pray enough, or trust enough. But implicit assumptions about cause and effect are sadly simplistic.

There is nothing quite as destructive to a person living with chronic illness as the kind of remark that usually takes this form: “We are praying so hard for you. We just cannot figure out why you don’t get well.” The implication is that somehow the person living with the ailment is at fault. It’s Job’s friends in twenty-first-century clothing, still looking for fault, still blaming the victim. They are often afraid to embrace the reality of God suffering with us.

LECTIO DIVINA AND CHRONIC ILLNESS

… Each person, each illness, is a particular story – a story told through a particular person in his own context, in her own time and place. Each story is full of sacred meaning. Discerning the meaning, listening for intimations of divine presence in the midst of confusion, disorientation, and pain requires what the Benedictine tradition calls “listening with the ear of the heart.”

… With lectio divina as a guide, the spiritual life of one who is ill begins to be reshaped. The irreducible, immediate presence of God revealed in and through the suffering, in and through the lectio divina, upends old patterns. Something new begins to take form from the ground up. The body that is broken becomes the locus for a spiritual life that is grounded in the everyday reality of living with illness. Broken Body, Healing Spirit: Lectio Divina and Living with Illness offers a way of engaging in the spiritual practice of lectio divina as one listens to the text of a body that is ill, of a life that is afflicted.

Excerpt from Broken Body, Healing Spirit: Lectio Divina and Living with Illness by Mary C. Earle. Published with permission.

Mary C. Earle

Mary is an Episcopal priest, poet, author, spiritual director and retreat leader. Until her retirement, she taught classes in spirituality for the Seminary of the Southwest in Austin, Texas. Mary has authored nine books, including: Days of Grace: Meditations and Practices For Living Well With Illness and Beginning Again: Benedictine Wisdom for Living with Illness She has offered presentations and retreats in a variety of ecumenical settings, including conferences of the Academy for Spiritual Formation, Spiritual Directors International, the International Thomas Merton Society and hospice organizations, and has written articles for a variety of journals, including Presence: the Journal of Spiritual Directors International, Radical Grace, Reflections, and The Lutheran.

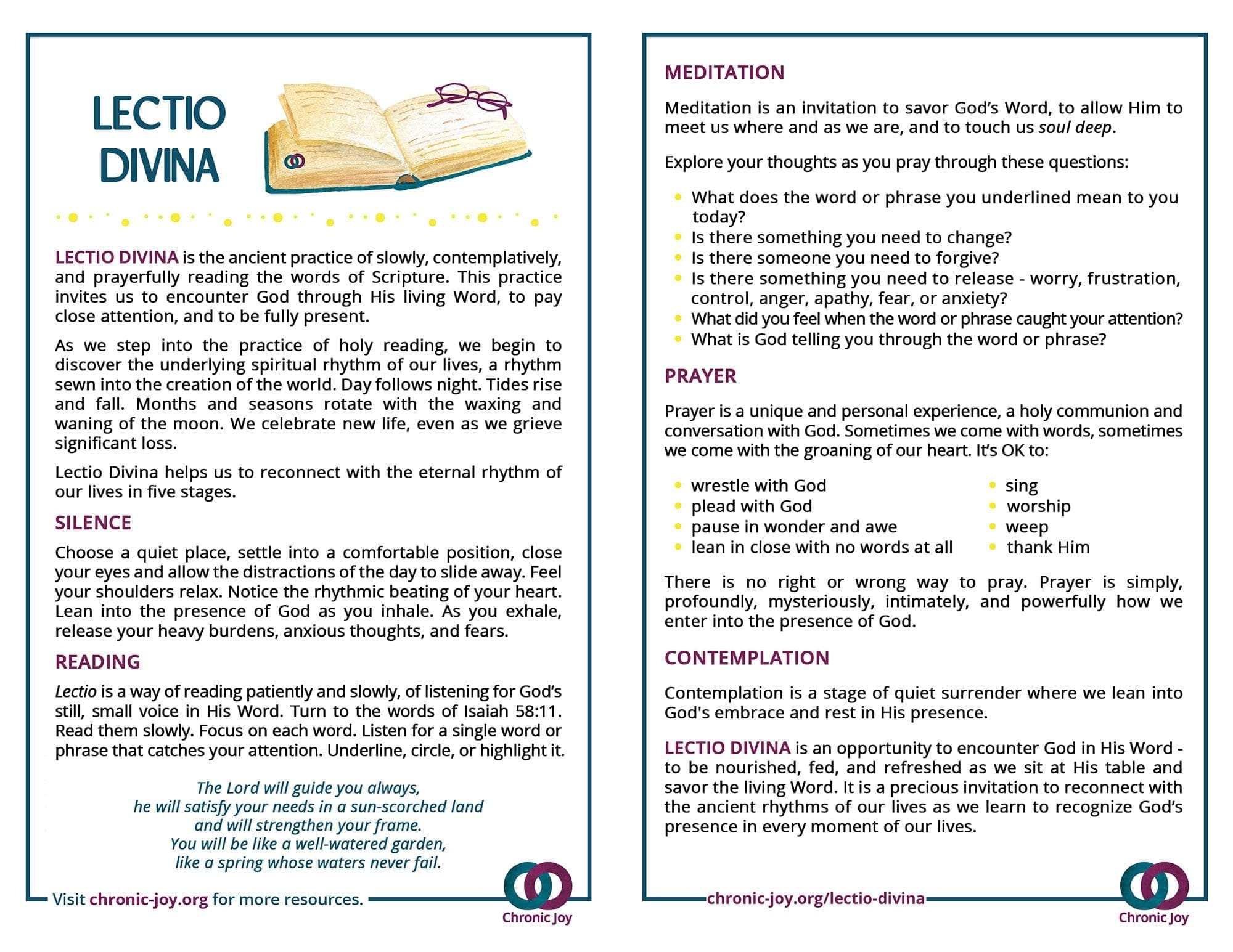

Lectio Divina

Lectio Divina is the ancient practice of slowly, contemplatively reading the words of Scripture, an invitation to encounter God through His Word, to pay close attention, and to be fully present.

Recent Comments