Words that did not sound like my own began welling up in me… As I filled out these images, crafting each into a poem, I found I was writing lament. (Abigail Carroll)

VOCABULARY OF THE HEART

I don’t know where the voice came from. Words that did not sound like my own began welling up in me, yet they were very much my own. They emerged as pleas addressed to the Divine with an urgency, brazenness, and depth that startled me, each imperative a longing expressed in metaphor: Make me river, Make me chalice, Make me plow blade, Make me willow. As I filled out these images, crafting each into a poem, I found I was writing lament.

As a spiritual exercise during hard seasons of life, I have intentionally chosen to write about topics of delight: finches, peonies, loosestrife bending in the wind at the edge of the lake—anything but darkness. However, during the particularly excruciating season of my life, out of which this series of poems flowed, I learned to lament in poetry—and lamenting in poetry taught me something important about prayer.

POETRY AND PRAYER

Prayer has often been compared to poetry, and with good reason. Like poetry, prayer emphasizes a careful choice of words. Because of each word’s careful, deliberate choice, the language of prayer (like the language of poetry) carries a greater meaning than casual conversation or mere prose. The words of a prayer are thick with significance, pregnant with possibility.

Like poetry, prayer contains pause. In both modes of expression, the silence surrounding words is as important as the words themselves. Both poetry and prayer engage the spirit, each in their own way. They are not merely a fanciful description of beauty on the one hand and a functional request for the divine provision of needs on the other, but each form is an occasion for deeply engaging the soul.

WHEN POETRY BECOMES PRAYER

Until recently, however, I would not have agreed with the statement that poetry is (or can be) prayer. I thought prayer is what you do on your knees before God—without the mediation of pen and paper. Can a painting, a sculpture, a tapestry, or another artistic expression be a prayer? My answer would have been “No.” I would have conceded they can certainly be prayer-like. They might even capture something of the spirit of prayer, but in the end, they are products, not prayer—each a creative articulation of feeling or thought designed more to engage others than God.

Perhaps my problem with poetry as prayer was due to poetry’s distinct self-awareness as art.

A good poet will not hesitate to spend an hour, even a day, choosing a single word. As a writer, I have tasted the delight of hours-long questing after the perfect turn of phrase. Art’s assiduous navigation of aesthetic options is inherent, and the work born out of that navigation is necessarily its own aesthetic statement. Try as we might, we can’t escape the fact that art revels in itself. It insists on putting forth its best and truest version of the longing it incarnates, and it will spare no length when it comes to honing and perfecting that expression.

So, if poetry (like all other art) is an aesthetic statement, how can it be prayer? Philosophically speaking, I cannot fully say, and I don’t have a theological explanation either. All I know is that when I began to pen my laments, not only did the poems emerge as prayers, but these prayers were wilder, more daring, and more honest than any prayer I might have fumbled through on my knees. They were also more pondered, nuanced, and (as pure byproduct) more beautiful.

THE POETRY OF LAMENT

The power in these laments may have been (in part) thanks to their heavy reliance on metaphor, a literary tool I don’t usually use in prayer but perhaps should. I don’t know what about the swollen green rivers of early April in Vermont drove me to write Make me river as I peered through the train window on my way south. Still, as I explored (through my pen) the sound, shape, and movement of water swirling in jade rock pools and coursing through the monotone landscape of not-yet-spring in the North, I began to realize that the stark, unawakened earth was a picture of my dormant soul.

The river was a picture of my desire to flow with life. A clarity about my spiritual state emerged from crafting this poem—and out of that clarity surfaced an ensuing petition: to be (as the poem puts it) unstilled. I did not start with this clarity or petition. Instead, the creative process drew this out of me.

Writing poetry puts me in touch with my deeper longings, helping me not merely to articulate them but to reorder them. Isn’t that, in so many ways, what prayer is: a reordering of our longings before God? Prayer on my knees (though I consider it of great importance) does not always accomplish this in quite the same way. There, I find myself asking for concrete and often predictable things such as healing for a loved one, peace when I’m experiencing anxiety, wisdom in a particular decision. When I am writing poetry, the creative process takes me to places in prayer I might not otherwise dare to go.

Out of the depths I cry to you, Lord; Lord, hear my voice. Let your ears be attentive to my cry for mercy. (Psalm 130:1-2)

WRITING PRAYER AS POETRY

I have come to believe that a poem can indeed be a prayer in every sense of the word—and what is more, writing a prayer as a poem can be a spiritually formative experience. Writing prayers as poems opened the door to lament for me, enabling me to voice before God a level of anguish I did not have the courage to verbalize in conventional forms of prayer.

In some ways, writing prayers as poems gave me a way to trick myself into praying what I did not feel free to pray. By the time I had drafted a complete poem, I realized I had very much (without meaning to) inhabited that poem as a prayer.

The line between prayer and art had become blurred.

For some, I imagine such a blurring between what is prayer and what is poem may cause unease about where piety ends and vanity begins. As for me, I am learning to see this blurring as an invitation. I believe that the very work of writing a prayer as poetry—of choosing each word as carefully as a mosaic-maker chooses each tessera of glass, marble, or tile—does more than make for a beautiful poem; it takes us deeper into our hearts than we might otherwise go, and it gives us a new vocabulary with which to offer our longings to God.

First published at Ruminate Magazine. Published with permission.

Prayer

Father, thank You for allowing us to approach You honestly with all our emotions. You have made us creative beings, and we can express ourselves to You in many ways. Even when we don’t have words, the Holy Spirit intercedes for us. As we cry out our laments, speak to us in the pauses. May we come to You just as we are today. In Jesus’ name, amen.

For Reflection

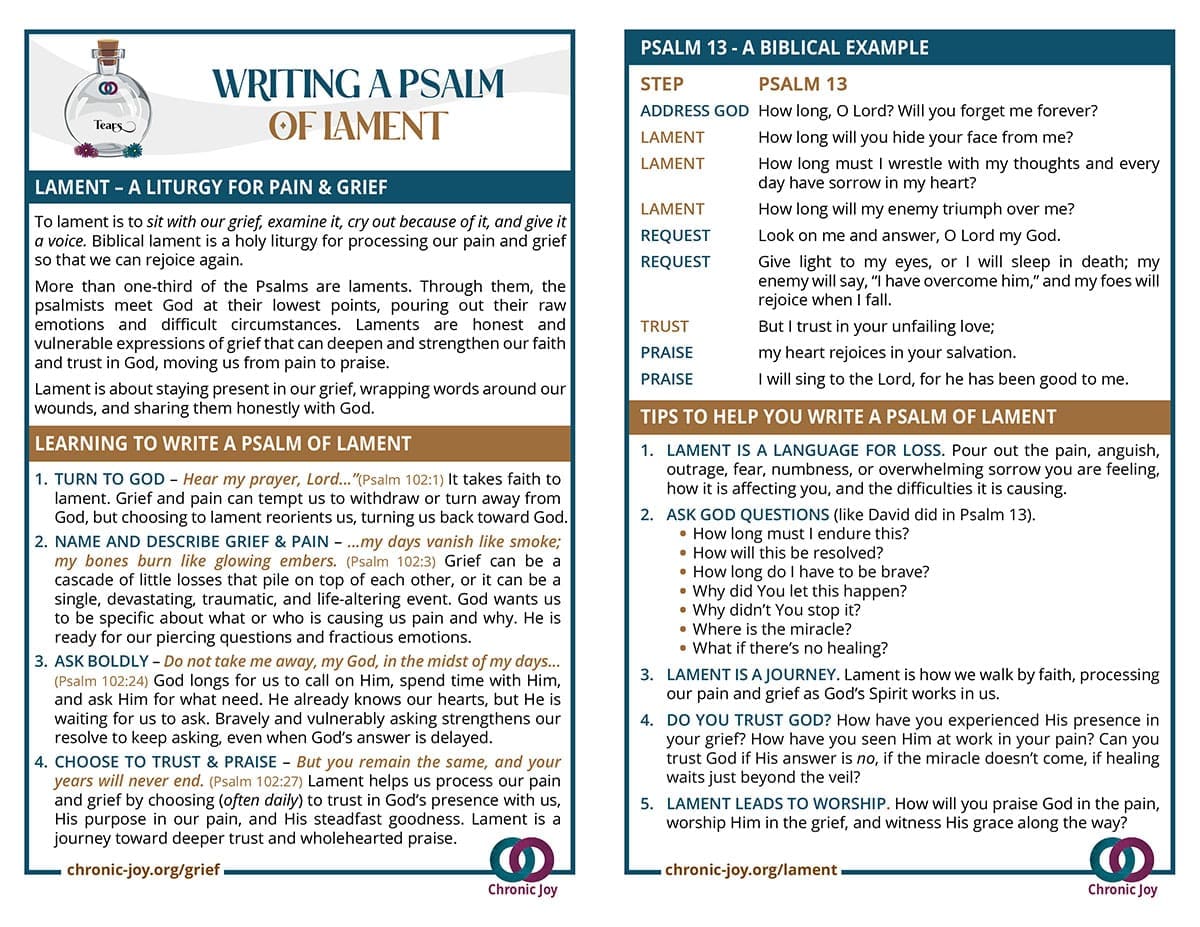

- Today, we invite you to step into lament through our beautifully written free printable and our deeply thoughtful Lament web page.

- What kinds of creative expression do you experience as prayer? Poetry? Painting? Dancing? Weaving? Cooking? Gardening? Other artistic expressions?

- Now switch gears and spend time seeking topics of delight: finches, peonies, loosestrife bending in the wind at the edge of the lake—anything but darkness. Breathe in the beauty; when you’re ready, begin to write.

Abigail Carroll

Abigail is the author of two collections of poetry [Habitation of Wonder (Wipf & Stock, 2018) and A Gathering of Larks: Letters to Saint Francis from a Modern-Day Pilgrim (Eerdmans, 2017)] as well as a work of nonfiction [Three Squares: The Invention of the American Meal (Basic Books, 2013)]. She serves as pastor of arts and spiritual formation at Church at the Well in Burlington, Vermont. In her free time, she enjoys gardening, photographing nature, and sipping a well-brewed cup of tea.

Lament

Step in slowly. Sit with God. Allow yourself time and space to feel and experience your pain. When you’re ready, take up your pen and explore the precious and life-giving gift of lament.

Recent Comments