TRUST AND LAMENT

Last March, I spent my birthday with a group of women at a retreat center in northern Ohio—a beautiful, former girls’ school turned nunnery turned sanctuary. There, our hearts were primed to hear God’s voice. Each morning, I led the women in Lectio Divina. We walked a prayer labyrinth on the property and prayed under birdsong mingled with the voices of tall, limber pines singing in the wind. When the time came to give my message, I was changed. I felt close to these women…safe…and God kept nudging me to give a different message than the one I’d prepared. I felt the urge to share more deeply and be vulnerable.

WHEN THE SOB ESCAPED

So I did. In the context of Scripture, I shared the story of a difficult experience my family had just been through—something that had caused great pain that still touched us in many ways. As I was speaking the words out loud, something so surprising happened. I felt a sob well up in my throat, and there was nothing I could do to suppress it. I had never told this story publicly, and my emotions took me off guard, but when that sob escaped, something beautiful happened. Every eye turned unblinkingly upon me. The tears had captured their attention. After all, this is something they all understood so well: sorrow, grief, the deep soul disappointment that life sometimes hands us. I looked at the faces of the women I spoke to and saw only love.

After a time of worship, as we clustered in small groups sipping coffee and nibbling sweets, woman after woman approached me. In hushed tones, they shared similar stories of darkness, times of despair, and pain. With few exceptions, these women told me how they kept their pain a secret, held tightly to their hearts, locked behind cut-flower words and plastered-on smiles only gum-deep.

My heart broke as I listened, and the realization sank into me: we do not feel safe sharing our pain, our brokenness, our humanity, in our churches.

I remembered my time at that retreat this morning when, in my quiet time, I read Psalm 31.

Psalms – Praises

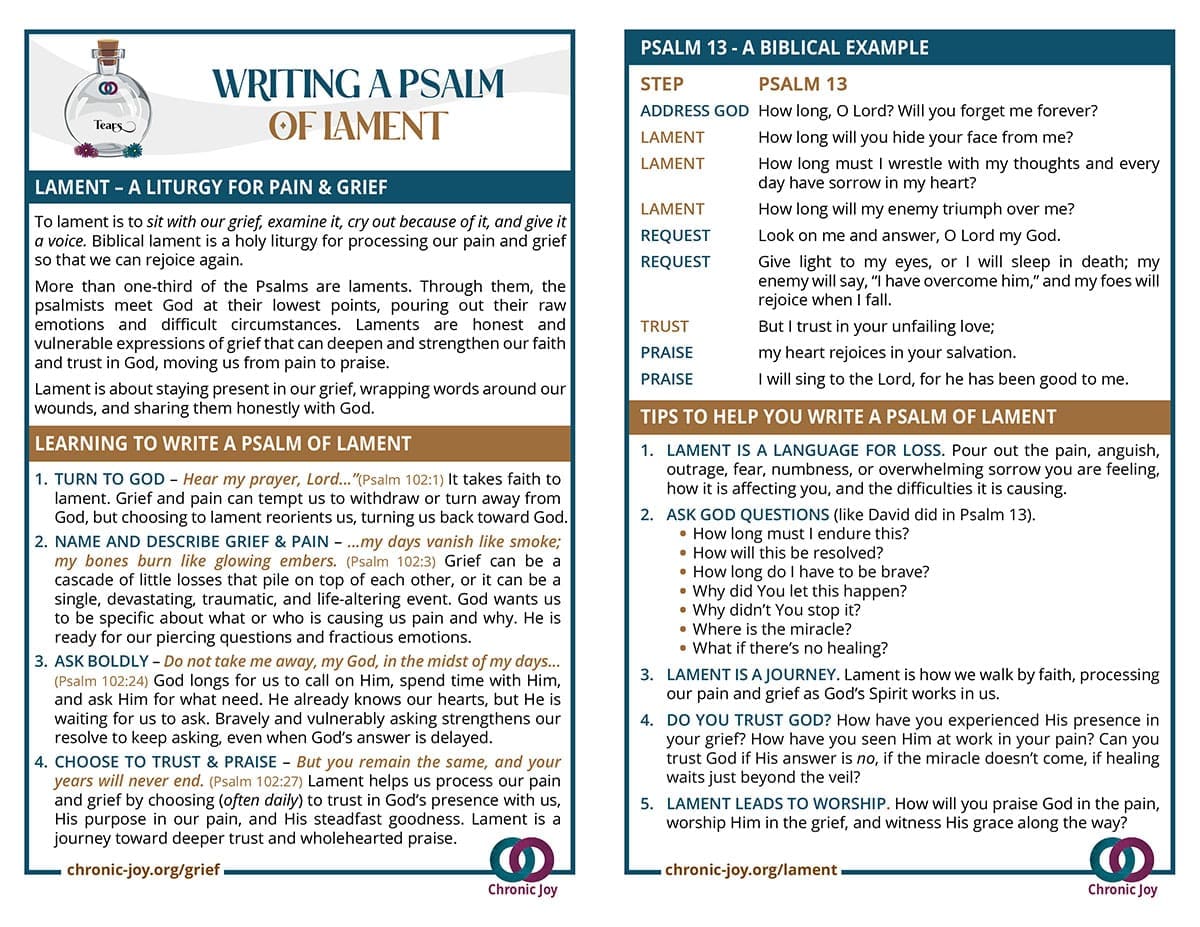

Eugene Peterson says the Psalms are where we go to learn our language as it develops into maturity, as it answers God. The Psalms are fraught with humanity, giving breath to a complete human experience. This particular Psalm is often used as part of the lectionary on Palm Sunday. It’s a typical lament, a cry for help, plus a complaint that moves through petition toward a statement of trust and praise. A large portion of the Psalms could be categorized as lament. The estimates are from one-third to one-quarter of the Psalms fall in this category…but the word Psalm means “praises” in Hebrew. Does it seem odd that a book of praises would hold so many laments—or do we need to change our definition of praise?

Why is this Psalm often chosen to accompany Palm Sunday? It certainly lends very little triumph to the triumphal entry. What it does do is boldly hold that tension that often so colors the human experience. A lament does the unthinkable: it holds anguish and hope side-by-side, revealing the depth of the nature of human life, allowing the humanity of Jesus to call out to our humanity.

When I read the story of the Triumphal Entry, I cannot help but wonder what was going through Jesus’ mind as he wrapped his legs around the soft underbelly of that donkey, the noise of the crowd ringing in his ears. He knew what was ahead. He’d already tried to explain to his disciples on two different occasions that he was going to his death—no heavenly army swooping in, no Roman defeat, no redemption of all the years of oppression his people had faced. What was he thinking?

Jesus was fully human. It was Pilot who said it: “Behold the man!”

But do I—behold the man? Too often, I want to impose upon Jesus some kind of superpower, but Jesus was a man. Fully God, yes, but fully human as well. How could one made of flesh and bone, one whose blood ran as hot and cold as ours, withstand such horrors? How could he plead with God to take away this cup and still end by saying, “Yet not what I will, but what you will?” Jesus felt the full range of human emotions, yet he was as close to the Father as any human could be: anguish and hope held side by side.

Dan Allender reminds us, “The poetry of the psalms were the hymns of the people of God. It was their songbook. It was what they sang in the temple at their worship services. The psalms are often thought to be the private poetry of people who struggled with God … [but] God intends for lament to be part of worship, and he intends for it to be done in community.”

How many times must our Lord have sung the Psalms, given his voice to lament? Even on the night of his arrest, we are told that after sharing the Passover feast, he and his disciples sang a hymn and then went to the Mount of Olives. Jewish tradition is to sing the Hallel Psalms (Psalms 113-116) as part of Passover. If Jesus did sing Psalm 116 on the night of his arrest, he sang these words: The snares of death encompassed me, the pangs of Sheol laid hold on me; I suffered distress and anguish. Then I called on the name of the LORD: “O LORD, I beg you, save my life!”

LAMENT CUTS THROUGH INSINCERITY

Lament cuts through insincerity, unveils pretense, and leads to trust and wonder because true worship involves bringing every aspect of our lives before God—not ignoring the hard stuff of life but worshipping amid our struggles.

Jesus prayed a portion of Psalm 31 from the cross: Into your hands, I commit my spirit. What a beautiful statement of trust!—but don’t you think (if he had sung this Psalm before) that the rest of the Psalm was also on his mind? The hard stuff comes after that sweet statement of trust:

Be merciful to me, O LORD, for I am in distress; my eyes grow weak with sorrow, my soul and my body with grief…

Jesus knew the power of lament. He knew the power of sharing sorrow publicly. To lament together is to allow the sorrows and joys of my brothers and sisters to be mine and mine to be theirs. This requires me to stay awake to sorrow, the struggle of my pain, and the questions of God. We can only lament when we fully trust, for lament opens the heart to wrestle with God and hold onto him through the pain—to allow ourselves to be touched by God so that we may walk with a limp, but we will be named.

After I shared that vulnerable message at that women’s retreat, one of the ladies (an artist) told us about the Japanese art of Kintsugi (or kintsukuroi). It’s a 500-year-old method for repairing broken pottery. You see, she said, most families only had one good bowl or platter in those ancient times. If it was broken, repair was necessary. Over time, artisans began repairing the cracks with a special lacquer mixed with gold—so that a bowl highly valued by the family may have many gold-veined lines. The golden seams became a sign of value instead of disrepair, the cracks a vehicle to appreciate the beauty in brokenness.

WASHED IN THE BLOOD OF JESUS

The Psalmist says, “I have become like broken pottery.”—as we all are. We are a flawed people living in a fallen world, but we have been healed with something far more precious than gold lacquer. We are washed in the blood of Jesus—but we remain in this in-between time: redeemed but waiting, broken but beloved. This is our reality: in this life, we will have troubles. We are free to weep before God and one another. We are free to ask, “Why?”

When we come to him with our sorrow, it is only then that He can hold us. Only then can he etch gold throughout the broken places in our lives. If Jesus did not shy away from lament, why should we? Let us weep together and rejoice because even in sorrow, we have a luminous hope because we know death has already been defeated, and one day, it will no longer have its sting.

Our times are in Your hands, O LORD. Let Your face shine on Your servants. Save us in Your unfailing love. Amen.

Laura J. Boggess

Lament

Step in slowly. Sit with God. Allow yourself time and space to feel and experience your pain. When you’re ready, take up your pen and explore the precious and life-giving gift of lament.

Recent Comments